The Parliament has passed the Tribunals Reforms Bill 2021, which has provisions relating to the tenure, age criteria, and search-cum-selection committee for tribunal appointments. However, the new bill has once again tried to reintroduce similar provisions to the ones struck down by the Supreme Court earlier, giving rise to the possibility of a new challenge in the apex court.

Dimensions

- What are Tribunals and their need

- Provisions of the Bill

- How does the Bill Contradict SC Judgement?

- SC on the vacancy on Tribunals

- Suggestions

Content:

What are Tribunals and their need:

- The definition of Tribunals cannot be found in any legislation but in numerous judgements, the judiciary has clarified that there is a clear distinction between tribunals and courts.

- Tribunals are authorities that are quasi-judicial in nature that are set up especially by the act of parliament.

- They are constituted with the objective of delivering speedy, inexpensive and decentralised adjudication of disputes in various matters.

- They are created to avoid the regular courts’ route for dispensation of disputes.

- They run in parallel to the courts and generally are less formal, less expensive and less time consuming.

- In India, some tribunals are at the level of subordinate courts with appeals lying with the High Court, while some others are at the level of High Courts with appeals lying with the Supreme Court.

- There are two main reasons for establishing tribunals: allowing for specialised subject knowledge for technical matters, and reducing the burden on the court system.

Constitutional Provisions:

- They were not originally a part of the Constitution.

- The 42nd Amendment Act introduced these provisions in accordance with the recommendations of the Swaran Singh Committee.

- The Amendment introduced Part XIV-A to the Constitution, which deals with ‘Tribunals’ and contains two articles:

- Article 323A deals with Administrative Tribunals. These are quasi-judicial institutions that resolve disputes related to the recruitment and service conditions of persons engaged in public service.

- Article 323B deals with tribunals for other subjects such as Taxation, Industrial and labour, Foreign exchange, import and export, Land reforms, Food, Ceiling on urban property, Elections to Parliament and state legislatures, Rent and tenancy rights.

Problems with Tribunals in India:

- Huge unfulfilled Vacancy: Different qualification requirements for different tribunal leads to a high level of vacancy in the appellate tribunals. For example, In 13 tribunals alone, nearly 138 posts lying vacant out of 352 posts.

- Poor Adjudication & Delay in Judgement: The 272nd Law Commission Report mentions the Tribunals such as Central Administrative Tribunals and others had a pendency of 2.5 Lakh cases. Combined with the Vacancy they cannot determine the appeals. So the ordinance is necessary.

- Lack of independence: An interim report titled, Reforming The Tribunals Framework in India mentioned that the tribunals are not independent. The Executive holds key positions in Tribunals and the government is the biggest litigant. So the cases might not be decided fairly. So, the ordinance by shifting the appeals to the Judiciary will enable fair trial.

- Non-uniformity across tribunals with respect to service conditions, tenure of members, varying nodal ministries in charge of different tribunals. This created and contributed to malfunctioning in the managing and administration of tribunals.

- Ad-hoc regulation of Tribunals: The tribunals fall under various ministries subjects to frequent ad-hoc regulatory changes. By abolishing the appellate tribunals there won’t be any such possibility for ad-hoc regulations.

Bypassing the jurisdiction of the High Court in certain Tribunals: Few tribunals like NGT, NCLAT, CAT, etc have provisions allowing for direct appeals to the Supreme Court. Even though the Supreme court in the L. Chandra Kumar case criticised them for such practice. The Supreme Court held that it will create congestion in SC and also make the Justice costly and inaccessible.

Provisions of the Bill:

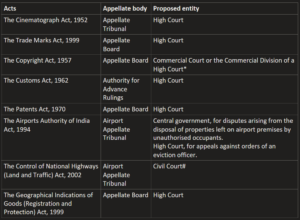

The Tribunals Reforms Bill, 2021 seeks to dissolve certain existing appellate bodies and transfer their functions (such as adjudication of appeals) to other existing judicial bodies

Amendments to the Finance Act, 2017:

- The Finance Act, 2017 merged tribunals based on domain. It also empowered the central government to notify rules on: (i) composition of search-cum-selection committees, (ii) qualifications of tribunal members, and (iii) their terms and conditions of service (such as their removal and salaries).

- The Bill removes these provisions from the Finance Act, 2017.

- Provisions on the composition of selection committees, and the term of office have been included in the Bill.

- Qualification of members, and other terms and conditions of service will be notified by the central government.

Search-cum-selection committees:

The Chairperson and Members of the Tribunals will be appointed by the central government on the recommendation of a Search-cum-Selection Committee. The Committee will consist of:

- (i) the Chief Justice of India, or a Supreme Court Judge nominated by him, as the Chairperson (with casting vote),

- (ii) two Secretaries nominated by the central government,

- (iii) the sitting or outgoing Chairperson, or a retired Supreme Court Judge, or a retired Chief Justice of a High Court, and

- (iv) the Secretary of the Ministry under which the Tribunal is constituted (with no voting right).

State administrative tribunals will have separate search-cum-selection committees. These Committees will consist of:

- (i) the Chief Justice of the High Court of the concerned state, as the Chairman (with a casting vote)

- (ii) the Chief Secretary of the state government and the Chairman of the Public Service Commission of the concerned state,

- (iii) the sitting or outgoing Chairperson, or a retired High Court Judge, and

- (iv) the Secretary or Principal Secretary of the state’s general administrative department (with no voting right).

The central government must decide on the recommendations of selection committees preferably within three months from the date of the recommendation.

Eligibility and term of office:

- The Bill provides for a four-year term of office (subject to the upper age limit of 70 years for the Chairperson, and 67 years for members).

- Further, it specifies a minimum age requirement of 50 years for appointment of a chairperson or a member.

How does the Bill Contradict SC Judgement?

The provisions of the bill are similar to certain provisions of the Tribunals Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance 2021, which were struck down by the Supreme Court last month.

Comparison with Tribunals Rules 2017 and SC judgement

- In March 2017, the Finance Act, 2017 reorganised the tribunal system by merging tribunals based on functional similarity. The total number of Tribunals was reduced from 26 to 19.

- It delegated powers to the central government to make Rules to provide for the qualifications, appointments, term of office, salaries and allowances, removal, and other conditions of service for chairpersons and members of these tribunals.

- The Department of Revenue, in 2017, under Section 184 of the Finance Act, 2017 notified the “Tribunal, Appellate Tribunal and other Authorities Rules”, 2017.

- These rules specified details of qualifications of the Tribunal members, their terms and conditions of service, and composition of the search-cum-selection committees.

- The rules gave the Central Government wide-ranging powers for appointment of members to 19 Tribunals by amending 19 existing laws.

- The qualifications of persons who may be appointed as the Chairperson and judicial member of the National Green Tribunal (NGT) was revised.

- The membership of the Search-cum-Selection Committee for the post of Expert Members no longer contained the Chairperson of the NGT and a Sitting Judge of the Supreme Court, with the Chairperson of the Committee being a Government appointee.

- The Rules made the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) responsible for conducting the inquiry with a written complaint against any member of the NGT and made a reference to a committee to conduct an inquiry. The rules were silent on the composition of such a committee on the basis of whose recommendations, the government may remove the member from the NGT.

In November 2019, the Supreme Court struck down the 2017 Rules (Rojer Mathew Case).

The Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court termed the rules as unconstitutional for being violative of principles of independence of the judiciary.

The Court stated that the Rules did not meet the requirements laid down in earlier judgements mandating judicial independence in terms of:

- (i) composition of the Tribunals,

- (ii) the security of tenure of the Tribunal members, and

- (ii) composition of the search-cum-selection committees.

The Court directed the central government to reformulate the Rules.

Key concerns that the Court wanted addressed include:

- (i) short tenures which prevent enhancement of adjudicatory experience, and thus impact the efficacy of Tribunals, and

- (ii) lack of judicial dominance in selection committees which is in direct contravention of the doctrine of separation of powers.

Comparison with Tribunal Rules 2020

Firstly, Term of office for presiding officers and members violates principles laid down by the Supreme Court

- The Bill and the earlier Ordinance specify that the term of office for the Chairperson and members will be four years.

- On July 14, 2021, the Supreme Court struck down these provisions of the Ordinance.

- The Court stated that specifying four years of term of office violates the principles of separation of powers, independence of judiciary, rule of law, and equality before law.

- Over the years, the Supreme Court had stated that short tenure of members of a tribunal along with provisions of re-appointment increases the influence and control of the Executive over the judiciary.

- It also discourages meritorious candidates from applying for such positions as they may not leave their well-established careers to serve as a member for a short period.

- The Court has also noted that security of tenure and conditions of service (including adequate remuneration) are core components of independence of the judiciary.

- The Supreme Court had stated that the term of office for the Chairperson and other members must be five years (subject to a maximum age limit of 70 years for the Chairperson and 67 years for other members).

Secondly, Minimum age requirement of 50 years for appointment as a member also violates earlier directions of the Supreme Court

- The Bill and the Ordinance specify that a person must be at least 50 years old to be appointed as a member of a tribunal.

- This violates past Supreme Court judgements and was also struck down by the Court in July 2021.

- While reviewing the Ordinance in 2021, the Supreme Court reiterated earlier judgements which emphasised the recruitment of members at a young age.

- In past judgements, the Supreme Court (2020) has stated that advocates with at least 10 years of relevant experience must be eligible to be appointed as judicial members, as that is the qualification required for a High Court judge.

- A minimum age requirement of 50 years may prevent such persons from being appointed as tribunal members.

SC on the vacancy on Tribunals

- No new judicial appointments have been made to tribunals since 2017 when the government first framed rules for a uniform appointment procedure to these quasi-judicial bodies.

- The Statement of Objects and Reasons of the 2021 Bill states that data from the past three years shows that the presence of tribunals in certain sectors has not led to faster adjudication, and such tribunals add considerable cost to the exchequer.

- It also states that these amendments would address the issue of shortage of support staff and infrastructure in such tribunals.

- However, transferring functions of an appellate body to a High Court may lead to a further increase in the disposal time of cases as most High Courts already have high pendency.

- The lack of human resources (such as inadequate number of judges) is observed to be one of the key reasons for accumulation of pending cases in courts.

- The Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice (2015) had noted that several tribunals (such as Cyber Appellate Tribunal and Armed Forces Tribunal) have vacancies which makes them dysfunctional.

- As of March 3, 2021, there were 23 posts vacant out of a total 34 sanctioned strength of judicial and administrative members in the Armed Forces Tribunal.

- The Committee stated that NTC being a dedicated independent agency for providing resources (includes infrastructural, financial, and human resource) to tribunals would help in resolving such issues.

- The Supreme Court (2019) considered the question whether amalgamation of tribunals could increase litigation, which in the absence of adequate infrastructure or budgetary grants, would overburden the judiciary.

- It noted the absence of such judicial impact assessment, and directed the central government to undertake an exercise to assess requirements and make sufficient resources for each Tribunal.

- Neither the Finance Act, 2017 which reorganised several Tribunals nor this Bill provide a Financial Memorandum that estimates the resources required as a result of their provisions.

- This defeats the purpose with which these tribunals were set up, which was to help reduce the burden on High Courts.

- Further, if there is an issue of shortage of administrative capacity at such tribunals, it may be questioned whether the capacity should be increased, or their case-load be shifted to other courts.

Suggestions

- SC has cautioned on the continuous creation of tribunals. So the Government has to stop creating new Tribunals and focus on bringing standardisation in Tribunals instead of abolishing them.

- The government has to amend the provisions of Tribunals that left High Courts out of its Jurisdiction.

- Adopting a methodology of a merger like the United Kingdom. The UK also suffered a similar problem to India with Tribunalisation. Further, both countries have similar administrative frameworks. This was highlighted by the Supreme Court in the NCLT Case. Further, the SC also mentions few significant recommendations.

- The Leggatt Report of the UK is also applicable to the problem faced by Tribunals in India. India has to create a single tribunals service and nodal agency based on the Leggatt Report. The Supreme Court also recommended the establishment of a National Tribunals Commission as an independent body to overview the functioning of tribunals.

- 74th Parliamentary Standing Committee Report on 2015 also mentioned a single nodal agency for monitoring Tribunals, Appellate Tribunals and Other Authorities

Mould your thought: The provisions of the Tribunal Reforms Bill 2021 give rise to the possibility of a new tussle between the central government and the Supreme Court. Evaluate.

Approach to the answer:

- Introduction

- Discuss the provisions of the tribunals Reform Bill

- Briefly write about the history of tussle between SC and government on the matter (since 2017)

- Discuss how the provisions of the new bill contradict Supreme Court directions

- Give suggestions to avoid such situation

- Conclusion