China’s national legislature has adopted a new law on the protection and exploitation of the land border areas, which could have bearing on Beijing’s border dispute with India.

Dimensions

- LAC issue

- Recent confrontations

- What does the new Law say?

- What does it mean for India?

- Way forward

Content:

LAC issue:

- After its independence, India believed it had inherited firm boundaries from the British, but this was contrary to China’s view.

- China felt the British had left behind a disputed legacy on the boundary between the two newly formed republics.

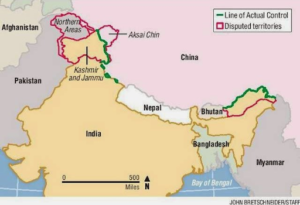

- The 3,488-km length border between India and China is not clearly demarcated throughout and there is no mutually agreed Line of Actual Control (LAC).

The India-China border is divided into three sectors, viz. Western, Middle and Eastern.

Western Sector –

- The dispute pertains to the Johnson Line proposed by the British in the 1860s that extended up to the Kunlun Mountains and put Aksai Chin in the then princely state of Jammu and Kashmir(or the Chinese province of Xinjiang).

- Independent India used the Johnson Line and claimed Aksai Chin as its own. However China stated that it had never acceded to the Johnson Line.

Middle Sector –

- The dispute is a minor one and is the only one where India and China have exchanged maps on which they broadly agree.

Eastern Sector –

- Here dispute is over the McMahon Line, (formerly referred to as the North East Frontier Agency, and now called Arunachal Pradesh) which was part of the 1914 Shimla Convention between British India and Tibet, an agreement rejected by China.

- Till the 1960s, China controlled Aksai Chin in the West while India controlled the boundary up to the McMahon Line in the East.

History of the dispute since independence:

- In 1960, based on an agreement between Nehru and Zhou Enlai, Chinese minister, discussions held by Indian and Chinese officials in order to settle the boundary dispute failed.

- The 1962 Sino-Indian War was fought in both of these areas.

- An agreement to resolve the dispute was concluded in 1996, including “confidence-building measures” (CBM) and the informal cease-fire line between India and China was officially accepted as the ‘Line of Actual Control’ in a bilateral agreement.

- In 2006, the Chinese ambassador to India claimed that all of Arunachal Pradesh is Chinese territory.

- In April 2013, as Chinese troops established a camp in the Daulat Beg Oldi sector, 10 km on their side of the Line of Actual Control, India retaliated by setting up camps on its side. Both sides pulled back soldiers in May and the tension got diffused.

- In 2014, China granted stapled visas to Indians from Arunachal Pradesh.

- In September 2014, India and China had a standoff at the LAC, when Indian workers began constructing a canal in the border village of Demchok, and Chinese civilians protested with the army’s support. It ended after about three weeks, when both sides agreed to withdraw troops.

- In September 2015, Chinese and Indian troops faced-off in the Burtse region of northern Ladakh after Indian troops dismantled a disputed watchtower the Chinese were building close to the mutually-agreed patrolling line.

- In June, 2017 a military standoff occurred between India and China in the disputed territory of Doklam (near the Doka La pass) , which is claimed by both China and India’s ally Bhutan.

- China’s claim on Doklam is based on the 1890 Convention of Calcutta between China and Britain for which Bhutan was not a party.

- The face-off at Doklam had also underscored the vulnerability of Siliguri Corridor, a 22 km-long narrow stretch linking the Northeast with the rest of India.

- On 28 August, India issued a statement saying that both countries have agreed to “expeditious disengagement” in the Doklam region.

Recent confrontations:

Following the incursion by Chinese soldiers across the LAC in eastern Ladakh in May 2020, the two countries have been engaged in military-level talks to defuse tensions amid massive troop deployment on both sides of the disputed border.

While there has been disengagement in the:

- Galwan Valley, Pangong Lake and Gogra – where Indian and Chinese soldiers clashed with blunt weapons in June last year

- the impasse continues in the Hot Springs and Depsang Plains in eastern Ladakh, which the 13th and latest round of talks between Chinese and Indian army corps commanders earlier in October failed to resolve.

Galwan Valley clash – June 2020

- On 15 June 2020, at patrolling point 14, Indian and Chinese troops clashed for six hours in a steep section of a mountainous region in the Galwan Valley.

- The immediate cause of the incident is unknown, with both sides releasing contradictory official statements in the aftermath.

- In the aftermath of the incident at Galwan, the Indian Army decided to equip soldiers along the border with lightweight riot gear as well as spiked clubs

- On 20 June, India removed restriction on usage of firearms for Indian soldiers along the LAC.

- Satellite images analysed by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute show that China increased construction in the Galwan valley since the 15 June skirmish.

Depsang Plains

- India–China tension at Depsang was reported by Indian media on 25 June 2020, which described movements of troops, heavy vehicles and military equipment.

What Does the New Law Say?

- The new law, which comes into effect from January 1, 2022, mandates China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to counter any “invasion, encroachment, infiltration, [or] provocation” along the country’s land borders.

- It also lays down a legal framework for hard border closures if the need arises.

- The law requires the Chinese government to take measures to “strengthen border defence, support economic and social development as well as opening-up in border areas”.

- It calls for improvements in public services and infrastructure in such areas to “encourage and support people’s life and work there”.

- The law also says citizens and organizations shall support border patrol and control activities and that the People’s Armed Police Force and the Public Security Bureau can be deployed to guard borders along with the PLA.

What does it mean for India?

It is a matter of concern as the legislation can have implications on the existing bilateral pacts on border management and on the overall boundary question.

Border Standoff and Disputes:

- Differences over the perception regarding the LAC have fuelled routine standoffs between Chinese and Indian soldiers.

- As the law unilaterally alters the situation in the India-China border areas, such stand offs could increase in the future.

Responsibility of the border clearly to the PLA — “as opposed to India”:

- With this new law, the chances of the PLA pulling back from any other area (in Ladakh) are remote as the PLA is now “bound to protect the integrity, sovereignty of the border”.

- It will make negotiations a little more difficult, a pullout from balance areas less likely.

New Dual civil military use settlements:

- China has been building “well-off” border defence villages across the LAC in all sectors, which means China is going to see resettlement of civil population closer to the LAC

- This could affect broader negotiations because China can claim that they have settle civilian population in the disputed areas.

Cross border Rivers / Lakes:

- The land border law also points to “measures to protect the stability of cross-border rivers and lakes”, which is “believed to have been made with India in mind”.

- Brahmaputra river which is an important river for India has its source in China’s Tibet Autonomous Region.

- It could be the case that “China’s government is trying to limit the volume of water during conflicts, citing ‘protection and reasonable use’ as stipulated in the law”.

India’s stand:

- The passage of this new law does not in India’s view confer any legitimacy to the so-called China Pakistan ‘Boundary Agreement’ of 1963 which government of India has consistently maintained is an illegal and invalid agreement.

- India expects that China will avoid undertaking action under the pretext of the law that could unilaterally alter the situation in the India-China border areas.

- India said, such a ”unilateral move” will have no bearing on the arrangements that both sides have already reached earlier — be it on the boundary question or for maintaining peace and tranquillity along the LAC.

Way forward:

- India and Bhutan are the two countries with which China is yet to finalize the border agreements, while Beijing resolved the boundary disputes with 12 other neighbors.

- The two sides could hold talks at the level of ministers or diplomats to break the deadlock before resuming military commander level talks.

- For this to materialize, peace and tranquillity in the border areas is a must.

Mould your thought: How does China’s new border law affect India’s interests in the Sino-Indian border? How can India proceed further to achieve its goals?

Approach to the answer:

- Introduction

- Discuss the India- China border dispute in brief

- Discuss the provisions of the new Chinese border law

- Mention how it can affect India

- Discuss the way forward

- Conclusion