The Australian outback has always harbored secrets, but few as precious as the recent discovery made by Indigenous Protected Area rangers in one of the continent’s most remote corners. What they found represents more than just scientific evidence—it’s a lifeline for one of the world’s most enigmatic creatures, a bird that vanished from human knowledge for nearly a century before reappearing like a ghost from the past. Such remarkable rediscoveries echo other extraordinary finds, like the 20,000-year-old cave etchings that revealed ancient cultural narratives thought lost to time.

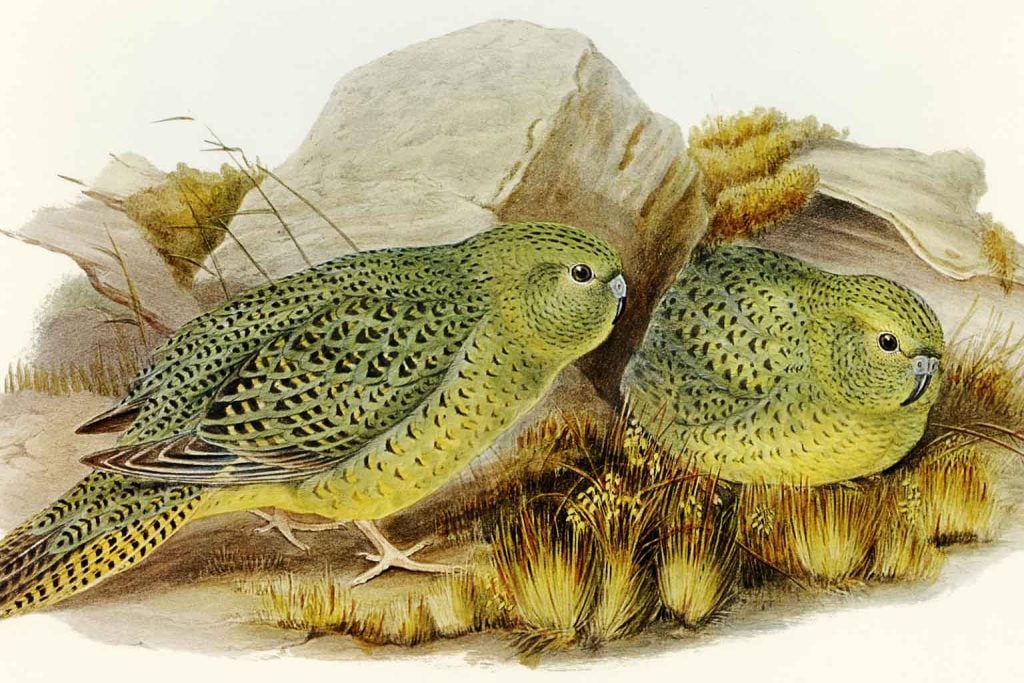

The night parrot, Australia’s most elusive avian species, has provided researchers with their most significant clue yet about its mysterious existence. This discovery comes at a critical juncture, as conservationists race against time to understand and protect a species that teeters on the edge of extinction. The find has ignited fresh optimism in scientific circles, offering unprecedented insights into breeding behaviors that have remained hidden since the species’ stunning rediscovery in 2013.

A Ghost Bird’s Return from Oblivion

The night parrot’s story reads like a conservation fairy tale with a bittersweet twist. For more than a century, this nocturnal wanderer existed only in museum specimens and fading field notes from early naturalists. Its presumed extinction became accepted scientific fact, with occasional unverified sightings dismissed as wishful thinking or misidentification.

The 2013 rediscovery sent shockwaves through the ornithological community. Suddenly, a species relegated to historical footnotes was thrust back into the spotlight, revealing just how little we understood about Australia’s own avifauna. The bird’s secretive nocturnal habits and preference for remote, inhospitable terrain have made systematic study nearly impossible, turning every piece of evidence into precious scientific currency.

According to research published in conservation genomics studies, the species’ extreme rarity may be both natural and human-induced. Unlike many bird species that form large flocks or maintain predictable territories, night parrots appear to exist as scattered individuals across vast landscapes, making population estimates extraordinarily difficult.

“Conservation genomics reveals the critically endangered Night Parrot exists in fragmented populations with extremely limited genetic diversity, making recovery efforts exceptionally challenging” – Conservation genomics research

The Predator Crisis Reshaping Australia’s Wilderness

The night parrot’s struggle for survival cannot be separated from Australia’s ongoing battle with invasive predators. Feral cats and European foxes have fundamentally altered the ecological balance across much of the continent, creating what experts describe as a predation crisis for ground-dwelling and low-nesting native species. This conservation challenge mirrors successful recovery stories elsewhere, such as the harpy eagle comeback in the Lacandon Jungle, where targeted predator control proved crucial.

Studies have shown that these introduced hunters possess advantages that native predators lack—they’re adaptable, prolific, and face no natural population controls. A single feral cat can kill hundreds of native animals annually, while fox populations have exploded across environments where they face minimal competition. For a species like the night parrot, which likely nests close to ground level in spinifex grasslands, these predators represent an existential threat.

The cascading effects extend beyond individual species loss. Environmental research demonstrates how the elimination of native seed dispersers and insect controllers disrupts entire ecosystems, creating feedback loops that make recovery increasingly difficult for surviving species.

Decoding the Mystery of Night Parrot Reproduction

The recent discovery by Ngururrpa Rangers represents a breakthrough in understanding the species’ most critical vulnerability: its breeding ecology. Night parrot researcher Nick Leseberg’s excitement about the find reflects years of frustration with a bird that seems to exist outside normal scientific methodology.

Traditional bird monitoring techniques—mist nets, territory mapping, nest searches—prove largely useless with a species that moves unpredictably across vast distances and calls only occasionally during brief nocturnal periods. The evidence uncovered by the Indigenous rangers provides the first concrete data about where and how these birds attempt to reproduce.

Studies from conservation biology research suggest that night parrots may require very specific environmental conditions for successful breeding, possibly linked to rainfall patterns, seed availability, or predator absence. This specialization, while helping them survive in harsh outback conditions, makes them extremely vulnerable to habitat disruption or climate variations.

The Psychological Weight of Conservation Under Pressure

Working with a species hovering on extinction’s edge creates unique psychological pressures rarely discussed in conservation literature. IPA coordinator Christy Davies’ emotional reaction to the discovery reflects the intense personal investment that rangers and researchers develop when dealing with critically endangered species. Such dedication to preserving cultural and natural heritage parallels the meticulous work seen in archaeological discoveries, like the ancient altar discovery at Tikal that revealed complex cultural relationships.

Professional conservationists often describe a form of chronic anxiety when working with species that could disappear during their watch. Every season without confirmed breeding becomes a source of mounting concern. Every habitat disturbance or predator sighting amplifies fears about population viability. The weight of potentially witnessing a species’ final extinction creates stress levels that mainstream conservation discussions rarely acknowledge.

Indigenous rangers bring additional perspectives to this emotional landscape, viewing species loss not just as scientific failure but as cultural erosion. Their traditional ecological knowledge often encompasses species relationships and behavioral patterns that Western science struggles to document, making their observations invaluable for understanding elusive species like night parrots. This integration of traditional knowledge with modern conservation mirrors how archaeologists combine historical records with new discoveries, such as the 3,000-year-old village unearthed in France, to build comprehensive understanding of past societies.

“Effective conservation management for critically endangered species requires integrating traditional ecological knowledge with modern scientific approaches to understand habitat requirements and population dynamics” – Conservation biology research

The night parrot’s future remains precarious despite this encouraging discovery. Its story illuminates broader questions about how we define conservation success when dealing with species that may naturally exist in extremely small numbers. Perhaps the real measure of progress lies not in population recovery to historical levels, but in maintaining the ecological conditions that allow such mysterious creatures to persist in our increasingly modified world.