The mountains of Shandong province have revealed their secrets slowly, and what archaeologists found there challenges everything we thought we knew about China’s ancient defensive strategies. A 2,800-year-old fortification, hidden for centuries in a remote mountain pass, has emerged from careful excavation work. This isn’t just another historical curiosity—it represents a fundamental shift in understanding how early Chinese states approached territorial defense, much like how 5,000-year-old fortification discoveries have revolutionized our understanding of ancient European defensive strategies.

The discovery predates the famous Great Wall by several centuries, but its significance extends far beyond simple chronology. This ancient stronghold tells the story of a fragmented China where rival states were already thinking strategically about large-scale military architecture. The fortification reveals sophisticated planning and permanent military presence at a time when most historical accounts suggest such organized defensive systems didn’t yet exist.

What makes this find particularly compelling is its context within the broader narrative of Chinese unification. The structure was built and expanded during periods of intense warfare between competing states, offering a window into military thinking that shaped the eventual creation of unified China.

A Strategic Chokepoint Centuries in the Making

The fortification began as a 33-foot-wide defensive wall around 800 B.C., during China’s period of political fragmentation. The state of Qi, which controlled parts of modern-day Shandong, clearly recognized the strategic value of this particular mountain pass. Archaeological evidence suggests this wasn’t a hastily constructed barrier but a carefully planned military installation designed for permanent occupation.

During the tumultuous Warring States period (475-221 B.C.), the fortification was dramatically expanded to 100 feet in width. This expansion reflects escalating military pressures and increasingly sophisticated siege warfare techniques. The presence of houses, roads, and trenches indicates a complete military infrastructure rather than a simple wall.

According to research published in archaeological chronology studies, radiocarbon dating of animal bones and plant remains has confirmed the structure’s ancient origins with remarkable precision. The dating methodology, applied to materials found in the same stratigraphic layer as the fortification, provides solid scientific backing for claims about the structure’s age and historical significance.

“Radiocarbon dating methods provide crucial chronological frameworks for understanding early Chinese archaeological sites, enabling precise temporal placement of ancient fortifications” – Archaeological chronology research

Redefining Ancient Chinese Military Architecture

This discovery forces historians to reconsider assumptions about when large-scale defensive architecture first appeared in China. The sophistication evident in the Shandong fortification suggests that territorial defense strategies were far more advanced during the pre-unification period than previously understood.

The permanent garrison stationed at this location indicates a level of military organization that challenges conventional timelines. Expert analysis suggests that Qi soldiers maintained continuous presence at this strategic point, transforming what might have been a temporary defensive measure into a lasting military installation, similar to how 3,000-year-old fortress discoveries in Jerusalem reveal sophisticated ancient defensive planning.

The structure’s design reveals deep understanding of tactical advantages offered by mountainous terrain. By controlling this specific pass, defenders could force enemy armies into vulnerable positions while maintaining superior strategic positioning. This level of military thinking demonstrates sophisticated battlefield awareness centuries before China’s eventual unification under the Qin dynasty.

The Complex Relationship with Great Wall History

While some reports have suggested this fortification extends Great Wall origins by 300 years, the relationship is more nuanced than simple chronological extension. Experts emphasize that this structure represents independent military architecture rather than an early version of the famous wall system that would later define Chinese defensive strategy.

The fortification differs significantly from the Great Wall of Qi, constructed in 441 B.C. as a massive barrier stretching over 200 miles. That later structure was eventually incorporated into the unified Great Wall system under Qin Shi Huang’s reign (221-210 B.C.). The Shandong discovery represents something different: localized defensive thinking focused on specific geographical advantages rather than broad territorial barriers.

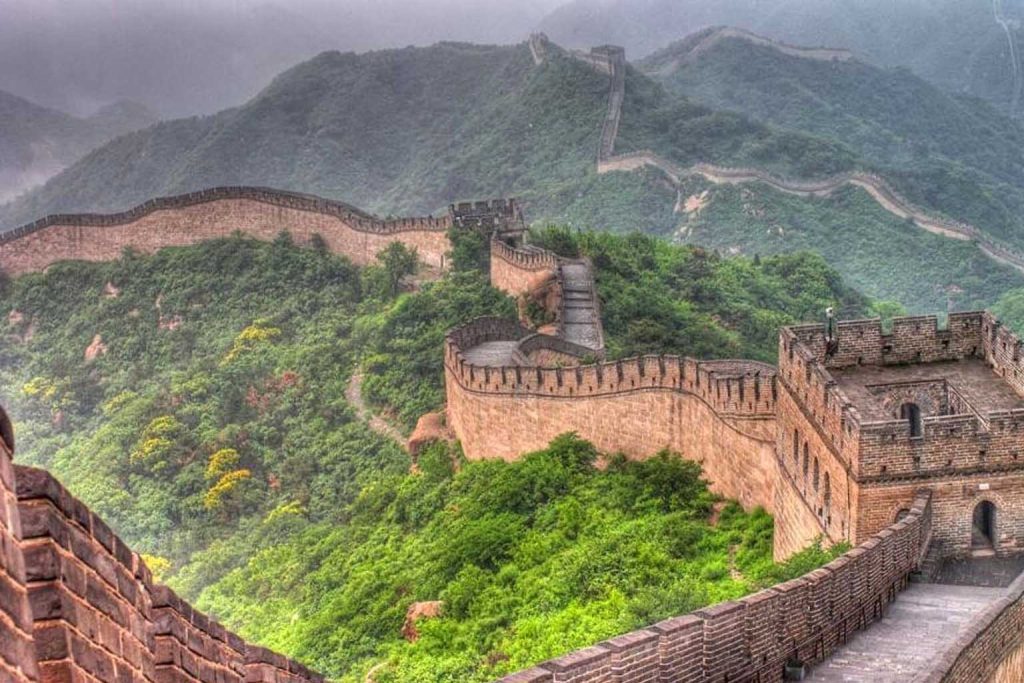

Historical records indicate that the eventual Great Wall emerged from linking various defensive walls built by separate states. The continuous modification and expansion of these structures, particularly during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), created the monument we recognize today. The Shandong fortification provides context for understanding how individual states approached defense before this unification process began.

The Strategic Geography Behind Ancient Warfare

Mountain passes have always represented critical strategic assets in military planning, and the Shandong discovery illustrates how early Chinese states understood and exploited geographical advantages. The fortification’s location wasn’t accidental—it represented careful analysis of terrain, enemy movement patterns, and defensive capabilities.

The permanent military presence established at this location suggests that controlling specific geographical bottlenecks was considered worth significant resource investment. The houses and infrastructure discovered alongside the fortification indicate that defending this pass required sustained commitment of personnel and materials over extended periods.

Research utilizing advanced archaeological dating methods into the site reveals evidence of continuous occupation and modification across several centuries. This pattern suggests that successive military leaders recognized the location’s strategic value and were willing to invest in maintaining and improving defensive capabilities as warfare techniques evolved.

“Stratigraphic analysis combined with radiocarbon dating provides archaeologists with powerful tools for establishing chronological sequences at complex ancient sites” – Archaeological methodology research

The Overlooked Implications for Understanding State Formation

The Shandong fortification reveals aspects of early Chinese state development that traditional historical accounts often minimize. The level of coordination required to construct, expand, and maintain such installations suggests that administrative capabilities of pre-unification states were more sophisticated than commonly believed.

The fortification required not just military vision but substantial logistical support. Moving construction materials to remote mountain locations, maintaining supply lines for permanent garrisons, and coordinating defensive strategies across multiple sites demanded organizational skills that challenge assumptions about early Chinese political development. This sophisticated approach to territorial control mirrors the complex cultural dynamics seen in other ancient civilizations, such as the 44,000-year-old narrative artwork that reveals advanced symbolic thinking in prehistoric societies.

Evidence from the site suggests that territorial control strategies were already well-developed centuries before unification occurred. The investment in permanent defensive installations indicates that state rulers were thinking beyond immediate military threats toward long-term territorial consolidation. This perspective offers new insights into how the eventual unification of China became possible—the administrative and military foundations were being established much earlier than previously recognized.

The discovery raises intriguing questions about how many similar fortifications remain hidden in China’s mountainous regions. If sophisticated defensive architecture was more common during the pre-unification period than historical records suggest, our understanding of ancient Chinese military capabilities and state organization may require significant revision. The Shandong fortification might represent not an exceptional case but rather a glimpse into a broader pattern of early defensive strategy that shaped China’s eventual political development, much like how 1,700-year-old altar discoveries at Tikal reveal complex political relationships in ancient Mesoamerica.