Deep beneath the Norwegian Sea, nearly two miles below the surface, a discovery is forcing scientists to reconsider fundamental assumptions about how our planet generates one of its most crucial chemical building blocks. What researchers found at hydrothermal vents in the Jøtul field wasn’t just unexpected quantities of hydrogen gas, but evidence that this hydrogen originates from an entirely different source than the scientific community had long believed.

For decades, the prevailing explanation for hydrogen production in deep-sea environments centered on serpentinization, a well-documented process where seawater interacts with mantle-derived rocks. Research published in PMC has extensively documented how hydrogen generation occurs during serpentinization of ultramafic rocks in hydrothermal systems. This mechanism seemed sufficient to account for the hydrogen that fuels entire ecosystems in the ocean’s most remote corners, including the remarkable microbial communities found at underwater formations. The new findings from the MARUM Center for Marine Environmental Sciences suggest this understanding captures only part of a much more complex chemical story.

The implications extend far beyond academic curiosity. Hydrogen serves as the primary energy source for countless deep-sea organisms that have never seen sunlight, forming the foundation of food webs that stretch across vast areas of the ocean floor. If scientists have been underestimating how much hydrogen these environments produce, they may also be underestimating the scope and resilience of life in Earth’s most extreme habitats.

A Chemical Process Hidden in Sediment

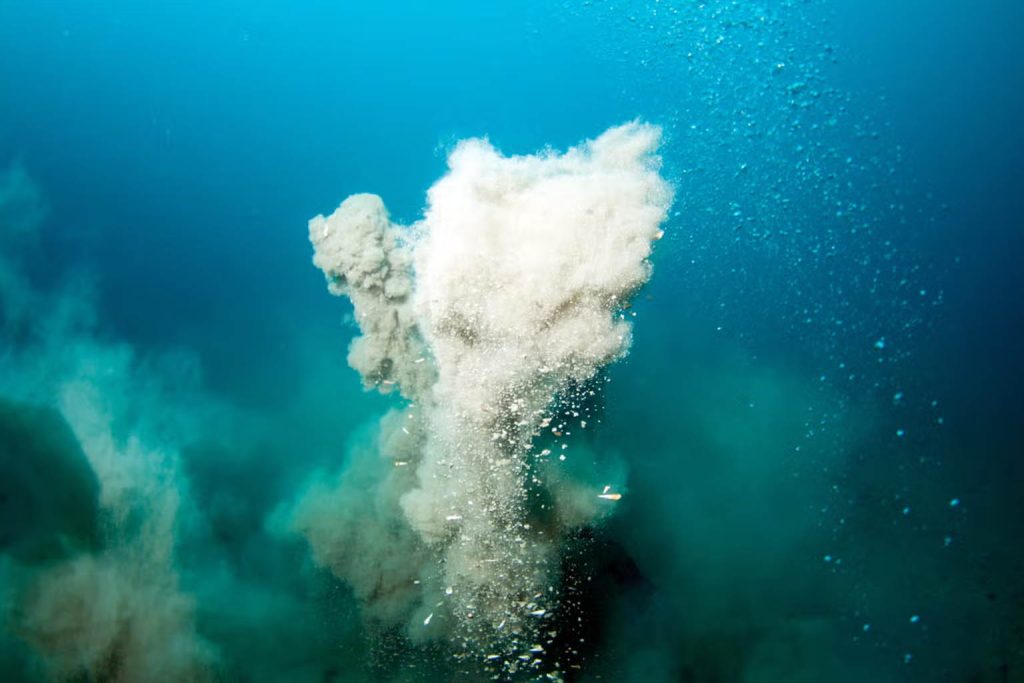

The research team, led by marine geochemist Alexander Diehl, encountered something unusual during their expeditions to the Knipovich Ridge. The hydrothermal vents they studied were piercing through thick layers of organic-rich sediments, creating conditions that existing models hadn’t adequately predicted. When they measured hydrogen concentrations reaching over 15 millimoles per liter, along with methane levels up to 66.3 millimoles per liter, the numbers didn’t align with what serpentinization alone should produce.

“Rock–water–carbon interactions during serpentinization demonstrate that ultramafic rocks exposed to water at temperatures below 400°C inevitably undergo complex chemical transformations” – Marine geochemistry research

Their thermodynamic modeling pointed toward a different mechanism entirely. Under the extreme conditions found at these depths, where water exists in a supercritical state, organic molecules buried in seafloor sediments undergo chemical breakdown that releases substantial quantities of hydrogen. This process operates alongside, rather than instead of, the rock-based reactions scientists had previously focused on.

The chemical signatures told a compelling story. Hydrogen sulfide levels remained surprisingly low compared to typical vent environments, while hydrogen and methane dominated the gas composition. This pattern strongly suggests that buried organic matter, rather than fresh mantle rock, was driving much of the chemical activity at these sites.

Technical Challenges and Breakthrough Methods

Part of what kept this hydrogen source hidden for so long was the sheer difficulty of accurately measuring gases from such extreme depths. Traditional sampling bottles lose pressure during the long ascent to the surface, allowing dissolved gases to escape before laboratory analysis can begin. Early attempts to quantify vent chemistry often provided incomplete pictures due to these technical limitations.

The breakthrough came with gas-tight samplers designed to maintain deep-sea pressure throughout the recovery process. This seemingly simple improvement allowed researchers to capture chemical signatures that had been literally escaping detection for years. The reliable measurements revealed not just higher hydrogen concentrations, but chemical ratios that pointed unmistakably toward sediment-based reactions. Just as LiDAR technology has revolutionized archaeological discoveries by revealing hidden structures, these advanced sampling techniques are uncovering previously invisible chemical processes in the deep ocean.

This methodological advance opens doors for studying other sediment-rich vent fields around the globe. Many similar environments may be producing hydrogen through buried organic matter breakdown, but previous sampling techniques weren’t sophisticated enough to detect or accurately measure the process.

Ecosystem Impacts Beyond the Immediate Vicinity

The discovery carries profound implications for understanding how deep-sea ecosystems function and adapt. Chemosynthetic microbes that convert hydrogen into biological energy form the base of food webs supporting everything from specialized bacteria to complex organisms like Bathymodiolus mussels. When hydrogen availability changes, these microbial communities shift, and those changes ripple through entire ecological networks.

What makes this finding particularly significant is that hydrogen doesn’t remain confined to the immediate vent area. Rising plumes carry it into surrounding waters, where it can fuel microbial activity at considerable distances from the original source. These microbes convert carbon dioxide into biomass, essentially creating biological productivity in regions far from any direct hydrothermal influence.

Research indicates that buried sediment reactions might be contributing far more to global biogeochemical cycles than current models account for. If this process occurs widely across sediment-covered vent fields, it could mean that deep-sea environments are more productive and chemically active than scientists have recognized. This discovery parallels how researchers studying ceremonial centers have found that ancient civilizations were far more sophisticated than previously understood.

The Overlooked Role of Organic Carbon Reservoirs

Most discussions of deep-sea chemistry focus on the dramatic interactions between seawater and fresh volcanic rock, but this research highlights how organic carbon deposits can serve as hidden chemical reactors. Studies published in Science Direct have shown that ultramafic rocks exposed to water undergo serpentinization reactions that form serpentine minerals, but this new research reveals additional pathways for hydrogen production. Seafloor sediments accumulate organic matter over geological timescales, creating vast reservoirs of carbon-rich material that becomes available for chemical reactions under the right conditions.

The process requires very specific circumstances: extreme temperatures, crushing pressures, and supercritical water conditions that break molecular bonds in ways that don’t occur in normal marine environments. This explains why the phenomenon remained undetected for so long. Only vents that penetrate deeply through organic-rich sediments while maintaining the necessary thermodynamic conditions can sustain this type of hydrogen production.

What remains unclear is how widespread these conditions are across the global ocean. Sediment-covered ridges exist in many locations, but each site presents unique geological and chemical characteristics. Some may produce hydrogen through this pathway, while others may rely primarily on traditional serpentinization processes.

Implications for Deep Ocean Exploration

The findings suggest that scientists need to reconsider how they approach deep-sea chemical mapping. Traditional models focused primarily on rock-water interactions may be missing significant hydrogen sources in sediment-rich areas. This has practical implications for understanding both current marine ecosystems and the potential for life in similar environments elsewhere.

Future research will likely need to examine sediment composition, organic carbon content, and burial history alongside traditional geological factors when predicting vent chemistry. The interplay between these factors may determine whether a particular site produces hydrogen primarily through rock reactions, sediment breakdown, or some combination of both processes. Understanding these complex systems becomes even more critical when considering the broader impacts on marine ecosystems in deep ocean environments.

As deep-sea exploration technology continues advancing, researchers may discover that this Norwegian Sea finding represents just one example of a much broader phenomenon. The ocean floor contains countless locations where organic-rich sediments meet extreme hydrothermal conditions, each potentially harboring similar chemical surprises that could reshape our understanding of how Earth’s most remote ecosystems sustain themselves across geological time.