The rolling hills of southeastern Turkey harbor a secret that predates the pyramids, Stonehenge, and virtually every monument we associate with early civilization. Göbekli Tepe, carved from limestone and assembled by human hands over 11,500 years ago, stands as humanity’s oldest known monumental architecture. Yet this archaeological marvel wasn’t built by farmers or city dwellers, but by societies we’ve traditionally viewed as nomadic hunter-gatherers.

The implications stretch far beyond archaeology. If mobile societies could organize massive construction projects millennia before agriculture supposedly enabled such feats, our entire timeline of human social development needs revision. The site forces uncomfortable questions about what we really know about our ancestors’ capabilities and motivations. Similar revelations continue to emerge across the ancient world, including a mysterious 4,000-year-old circular structure unearthed on Crete that challenges our understanding of Minoan civilization.

The discovery wasn’t recent, but understanding came slowly. German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt recognized the site’s true significance in the 1990s, decades after its initial identification. Research published in the Smithsonian Magazine confirms that limited carbon dating undertaken by Schmidt at the site validates the extraordinary age of this complex. What he found challenged every assumption about when humans first built for purposes beyond mere survival.

“The archaeologists did find evidence of tool use, with limited carbon dating undertaken by Schmidt at the site confirming this assessment of its remarkable antiquity” – Smithsonian archaeological research

The Engineering Puzzle That Shouldn’t Exist

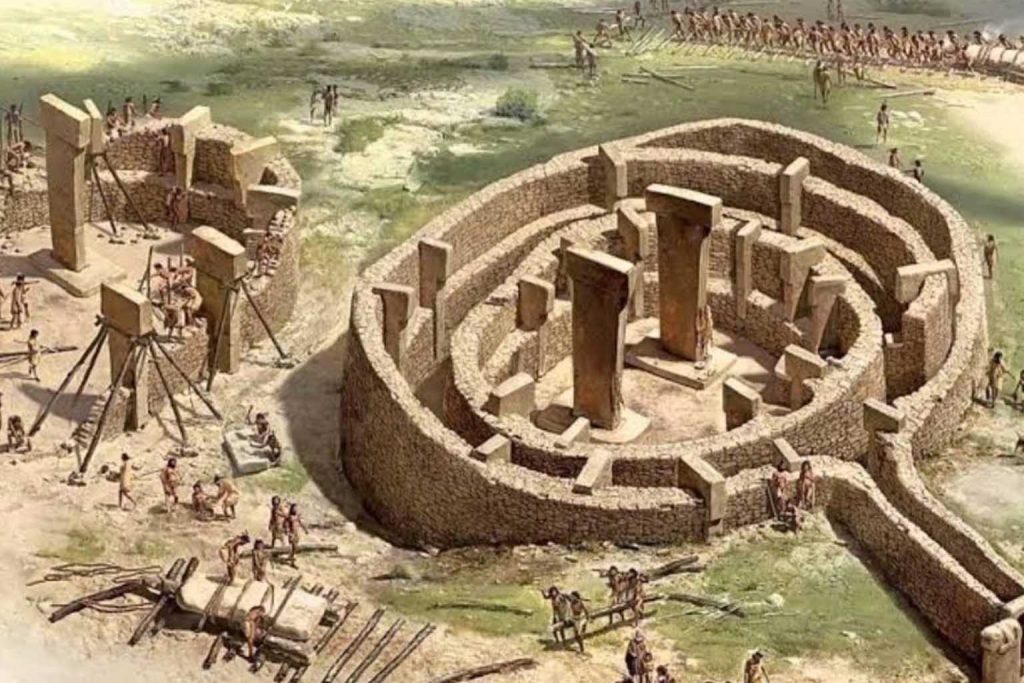

The sheer logistics of Göbekli Tepe’s construction defy conventional wisdom about prehistoric capabilities. Massive T-shaped pillars, some weighing up to 10 tons, were quarried directly from the bedrock and transported across the site without draft animals, metal tools, or wheels. The precision required to carve intricate animal reliefs into these monoliths suggests specialized craftsmen within societies supposedly focused solely on hunting and gathering.

The site’s architecture reveals sophisticated planning across multiple construction phases. Stone circles organized around central pillars create spaces clearly designed for group gatherings, yet the builders apparently had no permanent settlements. This contradiction forces archaeologists to reconsider the relationship between social complexity and sedentary life.

Recent excavations have uncovered evidence suggesting people may have actually lived at Göbekli Tepe, not just gathered there ceremonially. This finding would push back the timeline for permanent human habitation by centuries, fundamentally altering our understanding of the transition from nomadic to settled societies.

The Ritual Landscape Nobody Expected

The elaborate animal carvings covering Göbekli Tepe’s pillars tell stories we can barely interpret. Lions, foxes, snakes, and birds emerge from stone in configurations that clearly held meaning for their creators. Yet these aren’t random decorations—their placement and recurring motifs suggest systematic symbolic thinking.

Dr. Martin Sweatman’s research from the University of Edinburgh proposes that these carvings may represent astronomical alignments, potentially making Göbekli Tepe the world’s first calendar system. If accurate, this would demonstrate that systematic observation of celestial cycles preceded agriculture, not the reverse as commonly assumed.

The site’s circular structures, arranged in ways that facilitate group ceremonies, point toward complex social rituals. Yet without written records or clear cultural continuity, the specific nature of these gatherings remains opaque. Were they seasonal meetings between dispersed groups? Religious ceremonies? Social negotiations? The stones remember, but they don’t speak. Similar questions arise at other ancient sites, such as the lost temple in Peru that reveals ancient Andean spirituality, where organized religious practices emerged independently across continents.

Social Organization Beyond Current Models

Building Göbekli Tepe required unprecedented cooperation among prehistoric peoples. The coordination needed to quarry, transport, and precisely position massive stones suggests social hierarchies and specialized roles that weren’t supposed to exist among hunter-gatherer societies.

Archaeological evidence indicates the project spanned multiple generations, implying cultural continuity and knowledge transfer systems more sophisticated than previously attributed to non-agricultural societies. The builders maintained consistent architectural standards across centuries of construction, suggesting established traditions and possibly formal apprenticeship systems. Archaeological research published in recent studies emphasizes the importance of relying on stratigraphy, radiocarbon dating, and artifact analysis to understand these complex social structures.

The site’s scale also implies resource abundance that contradicts assumptions about prehistoric scarcity. These societies had sufficient food security to support large-scale construction projects, challenging models that portray pre-agricultural life as barely sustainable survival. This pattern of sophisticated ritual architecture appears across ancient civilizations, as evidenced by discoveries like the 1,700-year-old altar at Tikal that reveals complex cultural interactions between Maya and Teotihuacan societies.

“Archaeological evidence relies on stratigraphy, radiocarbon dating, and artifact analysis to separate factual discoveries from speculative narratives about these ancient societies” – Archaeological research methodology

The Deliberate Burial Mystery

Perhaps most puzzling is Göbekli Tepe’s abandonment and deliberate burial around 8,000 years ago. The builders didn’t simply leave—they carefully covered the entire complex with tons of earth and stone, preserving it for millennia. This massive undertaking rivals the original construction in scope and organization.

The timing coincides roughly with the regional development of agriculture, suggesting possible connections between changing lifestyles and the site’s closure. Did settled farming communities view the monument as obsolete? Was its burial part of broader cultural transformation? The intentional nature of the covering suggests profound ritual or social significance rather than natural abandonment.

Some researchers speculate that the burial preserved Göbekli Tepe for future generations, implying long-term thinking that further challenges assumptions about prehistoric planning capabilities. If intentional preservation was the goal, it succeeded spectacularly.

The Rarely Discussed Preservation Crisis

Modern excavation presents paradoxes that mirror the site’s ancient mysteries. Dr. Mehmet Onal’s estimate that complete excavation could require 150 years raises profound questions about archaeological priorities and methods. Current protective shelters shield exposed areas from weather damage, but they also limit access and alter the site’s relationship with its landscape.

The designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site ensures protection but creates new pressures. Growing tourism threatens the delicate stonework even as it provides funding for ongoing research. Balancing preservation with investigation requires decisions that will shape what future generations can learn from humanity’s oldest monumental architecture. Similar preservation challenges face other ancient sites, including the 5,000-year-old fire altar in Peru’s Supe Valley, where careful excavation continues to reveal secrets of the Caral–Supe civilization.

Most challenging is the recognition that current archaeological techniques may be inadequate for fully understanding the site. Deliberate delays in excavation acknowledge that future technologies might reveal secrets invisible to today’s methods. This patient approach contradicts typical academic pressures for immediate publication and results.

Göbekli Tepe stands as both revelation and riddle, forcing historians to acknowledge how little we truly understand about human social development. Its existence proves our ancestors were capable of monumental achievements millennia earlier than previously imagined, yet its purpose remains frustratingly opaque. Perhaps the site’s greatest lesson isn’t what it tells us about the past, but what it reveals about the limitations of our current assumptions about human capability and motivation.