In news– The latest draft of the Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022 (DPDP Bill, 2022) has now been made open for public comments recently.

Background:

- The current one is the fourth iteration of a data protection law in India. The first draft of the law — the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018, was proposed by the Justice Srikrishna Committee set up by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) with the mandate of setting out a data protection law for India.

- The government made revisions to this draft and introduced it as the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (PDP Bill, 2019) in the Lok Sabha in 2019.

- On the same day, the Lok Sabha passed a motion to refer the PDP Bill, 2019 to a joint committee of both the Houses of Parliament. Due to delays caused by the pandemic, the Joint Committee on the PDP Bill, 2019 (JPC) submitted its report on the Bill after two years in December, 2021.

- The report was accompanied by a new draft bill, namely, the Data Protection Bill, 2021 that incorporated the recommendations of the JPC.

- However, in August 2022, citing the report of the JPC and the “extensive changes” that the JPC had made to the 2019 Bill, the government withdrew the PDP Bill.

- Constant interactions with digital devices have led to unprecedented amounts of personal data being generated round the clock by users (data principals).

- The current legal framework for privacy enshrined in the Information Technology Rules, 2011 (IT Rules, 2011) is wholly inadequate to combat such harms to data principals, especially since the right to informational privacy has been upheld as a fundamental right by the Supreme Court ( K.S. Puttaswamy vs Union of India [2017]).

- It is inadequate on four levels;

- First, the extant framework is premised on privacy being a statutory right rather than a fundamental right and does not apply to processing of personal data by the government;

- Second, it has a limited understanding of the kinds of data to be protected;

- Third, it places scant obligations on the data fiduciaries which, moreover, can be overridden by contract and

- Fourth, there are only minimal consequences for the data fiduciaries for the breach of these obligations.

Key features-

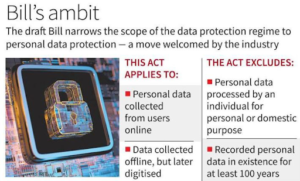

- The DPDP Bill, 2022 applies to all processing of personal data that is carried out digitally. This would include both personal data collected online and personal data collected offline but is digitised for processing.

- Furthermore, as far as the territorial application of the law is concerned, the Bill covers processing of personal data which is collected by data fiduciaries within the territory of India and which is processed to offer goods and services within India.

- The current phrasing, inadvertently, seems to exclude data processing by Indian data fiduciaries that collect and process personal data outside India, of data principals who are not located in India. This would impact statutory protections available for clients of Indian start-ups operating overseas, thereby impacting their competitiveness.

- This position further seems to be emphasised with the DPDP Bill, 2022 exempting application of most of its protections to personal data processing of non-residents of India by data fiduciaries in India.

- The current draft removes explicit reference to certain data protection principles such as collection limitation. This would allow a data fiduciary to collect any personal data consented to by the data principal.

- It also does away with the concept of “sensitive personal data”. Depending on the increased potential of harm that can result from unlawful processing of certain categories of personal data, most data protection legislations classify these categories as “sensitive personal data”.

- Illustratively, this includes biometric data, health data, genetic data etc. This personal data is afforded a higher degree of protection in terms of requiring explicit consent before processing and mandatory data protection impact assessments. By doing away with this distinction, the DPDP Bill, 2022 does away with these additional protections.

- Additionally, the Bill also reduces the information that a data fiduciary is required to provide to the data principal.

- Moreover, the DPDP Bill, 2022 seems to suppose that a notice is only to be provided to take consent of the data principal. This is a limited understanding of the purpose of notice.

- The DPDP Bill, 2022 also introduces the concept of “deemed consent”. In effect, it bundles purposes of processing which were either exempt from consent based processing or were considered “reasonable purposes” for which personal data processing could be undertaken under the ground of “deemed consent”.

- An important addition to the right of data principals is that it recognises the right to post mortem privacy which was missing from the PDP Bill, 2019 but had been recommended by the JPC.

- The right to post mortem privacy would allow the data principal to nominate another individual in case of death or incapacity.

- The reworked version of the legislation incorporates hefty penalties for non-compliance, but which are capped without any link to the turnover of the entity in question.

- It has also relaxed rules on cross-border data flows that could bring relief to the big tech companies, alongside a provision for easier compliance requirements for start-ups.

- The draft law leaves the appointment of the chairperson and members of the Data Protection Board entirely to the discretion of the central government.

- While the Data Protection Authority was earlier envisaged to be a statutory authority (under the 2019 Bill), the Data Protection Board is now a central government set up board.

- The new Bill has just 30 clauses compared to the more than 90 in the previous one, mainly because a lot of operational details have been left to subsequent rule-making.