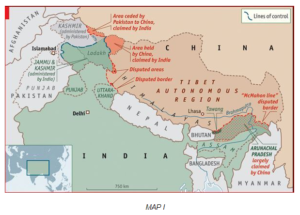

The LAC is the demarcation that separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory. India considers the LAC to be 3,488 km long, while the Chinese consider it to be only around 2,000 km. It is divided into three sectors: the eastern sector which spans Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim, the middle sector in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, and the western sector in Ladakh.

Disputed Regions in LAC

The alignment of the LAC in the eastern sector is along the 1914 McMahon Line, and there are minor disputes about the positions on the ground as per the principle of the high Himalayan watershed. This pertains to India’s international boundary as well, but for certain areas such as Longju and Asaphila. The line in the middle sector is the least controversial but for the precise alignment to be followed in the Barahoti plains.

The major disagreements are in the western sector where the LAC emerged from two letters written by Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai to PM Jawaharlal Nehru in 1959, after he had first mentioned such a ‘line’ in 1956. In his letter, Zhou said the LAC consisted of “the so-called McMahon Line in the east and the line up to which each side exercises actual control in the west”. Shivshankar Menon has explained in his book Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy that the LAC was “described only in general terms on maps not to scale” by the Chinese.

After the 1962 War, the Chinese claimed they had withdrawn to 20 km behind the LAC of November 1959. Zhou clarified the LAC again after the war in another letter to Nehru: “To put it concretely, in the eastern sector it coincides in the main with the so-called McMahon Line, and in the western and middle sectors it coincides in the main with the traditional customary line which has consistently been pointed out by China”. During the Doklam crisis in 2017, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson urged India to abide by the “1959 LAC”.

India rejected the concept of LAC in both 1959 and 1962. Even during the war, Nehru was unequivocal: “There is no sense or meaning in the Chinese offer to withdraw twenty kilometres from what they call ‘line of actual control’. What is this ‘line of control’? Is this the line they have created by aggression since the beginning of September?”. India’s objection, as described by Menon, was that the Chinese line was a disconnected series of points on a map that could be joined up in many ways; the line should omit gains from aggression in 1962 and therefore should be based on the actual position on September 8, 1962 before the Chinese attack; and the vagueness of the Chinese definition left it open for China to continue its creeping attempt to change facts on the ground by military force.

Independent India was transferred the treaties from the British, and while the Shimla Agreement on the McMahon Line was signed by British India, Aksai Chin in Ladakh province of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir was not part of British India, although it was a part of the British Empire. Thus, the eastern boundary was well defined in 1914 but in the west in Ladakh, it was not. Over years of Sino-Indian border talks, the Chinese side appeared to intentionally have an interest in preserving a degree of ambiguity about the line.

The strategic picture in the western sector of the LAC—Galwan River, Pangong Lake, Gogra-Hot Springs, and Depsang Plains—remains largely negative for India. Chinese People’s Liberation Army positions have expanded to unprecedented levels since the 1962 war between the two countries. At Pangong Lake, the Chinese side is in the process of setting up a helipad on territory that India perceives to be its own, in addition to substantially increasing its personnel counts to unprecedented levels in recent times. At a strategic river bend on the Galwan River, known to the Indian Army as “y-nalla” for its resemblance to a y-shaped bend in the valley, Chinese troops have set up a major encampment—also on territory India perceives to be its own.