- Brief on his political career

- Role in Economic Reforms

- Role in Security

- Role in Diplomacy

- Ayodhya incident and Babri Demolition

- Verdict on PV

Brief on his political career

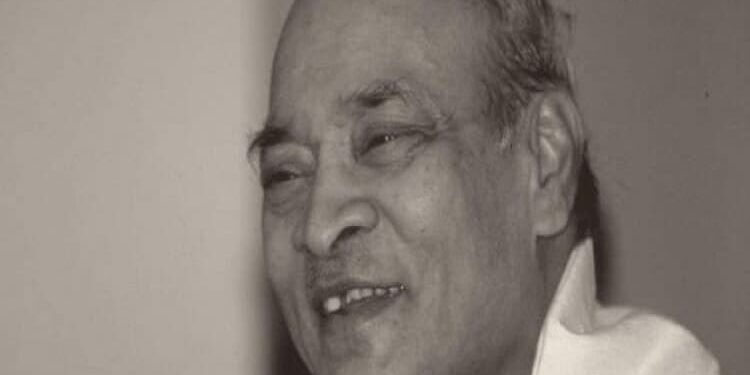

He led one of the most important administrations in India’s modern history, overseeing a major economic transformation and several incidents affecting national security. Rao accelerated the dismantling of the license raj. Rao, also called the “Father of Indian Economic Reforms,” is best remembered for launching India’s free-market reforms that rescued the almost bankrupt nation from economic collapse.

He was also commonly referred to as the Chanakya of modern India for his ability to steer tough economic and political legislation through the parliament at a time when he headed a minority government

His years as Prime Minister also saw the emergence of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), a major right-wing party, as an alternative to the Indian National Congress which had been governing India for most of its post-independence history.

Rao’s term also saw the destruction of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya which triggered one of the worst Hindu-Muslim riots in the country since its independence.

When the Indian National Congress split in 1969 Rao stayed on the side of then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and remained loyal to her during the Emergency period (1975 – 77). He rose to national prominence in 1972 for handling several diverse portfolios, most significantly Home, Defence and Foreign Affairs (1980-1984), in the cabinets of both Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi.

Rao very nearly retired from politics in 1991. It was the assassination of the Congress President Rajiv Gandhi that made him make a comeback. As the Congress had won the largest number of seats in the 1991 elections, he got the opportunity to head the minority government as Prime Minister.

He was the first person outside the Nehru-Gandhi family to serve as Prime Minister for five continuous years, the first to hail from South India and also the first from the state of Andhra Pradesh.

Role in Economic Reforms

Rao’s major achievement generally considered to be the liberalization of the Indian economy. The reforms were adopted to avert impending international default in 1991. The reforms progressed furthest in the areas of opening up to

- foreign investment,

- reforming capital markets,

- deregulating domestic business, and

- reforming the trade regime.

Rao’s government’s goals were

- reducing the fiscal deficit,

- Privatization of the public sector, and

- increasing investment in infrastructure

Rao’s finance minister, Manmohan Singh, an acclaimed economist, played a central role in implementing these reforms.

Rao almost immediately began efforts to restructure India’s economy by converting the inefficient quasi-socialist structure left by the earlier Prime Ministers into a free-market system.

His program involved cutting government regulations and red tape, abandoning subsidies and fixed prices, and privatizing state-run industries.

Those efforts to liberalize the economy spurred industrial growth and foreign investment, but they also resulted in rising budget and trade deficits and heightened inflation.

Role in Security

Rao energized the national nuclear security and ballistic missiles program, which ultimately resulted in the 1998 Pokhran nuclear tests. It is speculated that the tests were actually planned in 1995, during Rao’s term in office, and that they were dropped under American pressure when the US intelligence got the whiff of it. Another view was that he purposefully leaked the information to gain time to develop and test thermonuclear device which was not yet ready.

He increased military spending, and set the Indian Army on course to fight the emerging threat of terrorism and insurgencies, as well as Pakistan and China’s nuclear potentials.

It was during his term that terrorism in the Indian state of Punjab was finally defeated. Also scenarios of plane hijackings, which occurred during Rao’s time ended without the government conceding the terrorists’ demands.

Rao also handled the Indian response to the occupation of the Hazratbal holy shrine in Jammu and Kashmir by terrorists in October 1993. He brought the occupation to an end without damage to the shrine.

Rao’s crisis management after the March 12, 1993 Bombay bombings was highly praised. He personally visited Bombay after the blasts and after seeing evidence of Pakistani involvement in the blasts, ordered the intelligence community to invite the intelligence agencies of the US, UK and other West European countries to send their counter-terrorism experts to Bombay to examine the facts for themselves.

Role in Diplomacy

Rao also made diplomatic overtures to Western Europe, the United States, and China. He decided in 1992 to bring into open India’s relations with Israel, which had been kept covertly active since they were first established by Indira Gandhi in 1969 and permitted Israel to open an embassy in New Delhi.

He ordered the intelligence community in 1992 to start a systematic drive to draw the international community’s attention to alleged Pakistan’s sponsorship of terrorism against India and not to be discouraged by US efforts to undermine the exercise.

Rao launched the Look East foreign policy, which brought India closer to ASEAN.

He decided to maintain a distance from the Dalai Lama in order to avoid aggravating Beijing’s suspicions and concerns.

The ‘cultivate Iran’ policy was pushed through vigorously by him. These policies paid rich dividends for India in March 1994, when Benazir Bhutto’s efforts to have a resolution passed by the UN Human Rights Commission in Geneva on the human rights situation in Jammu and Kashmir failed, with opposition by China and Iran.

Ayodhya incident – Babri demolition

Members of the VHP demolished the Babri Mosque (which was constructed by India’s first Mughal emperor, Babar) in Ayodhya on 6 December 1992.

The site is believed by Hindus to be the birthplace of the Hindu god Rama and is believed by the Hindu Community to be a place of a Hindu temple created in the early 16th century.

The destruction of the disputed structure, which was widely reported in the international media, unleashed large scale communal violence, the most extensive since the Partition of India.

Hindus were indulged in massive rioting across the country, and almost every major city including Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Ahmedabad, Hyderabad, Bhopal struggled to control the Unrest.

He let L.K. Advani undertake the Rath Yatra, thus making majority communalism an acceptable form of mobilisation and advancing the Bharatiya Janata Party’s fortunes. The cost of state complicity and negligence was the demolition of Babri Masjid in 1992.Despite having the powers to take over the Babri Masjid and use armed forces to control the communal mob, the national government under PV’s watch played a spectator role. Communal carnage followed, and thousands lost their lives. To know more about the Ayodhya dispute click here

The best way to measure a Prime Minister’s contribution to nation-building would be to compare the state of the nation on the eve of one’s assumption of office with what one leaves behind at the end of one’s tenure. By that yardstick, Nehru was a great Prime Minister, despite all his foibles and errors of judgement. Indira Gandhi, too, left India a stronger nation than what it was when she inherited office. This cannot be said of any of the revolving door PMs of the 1980s and the 1990s.

PV’s tenure was unique in many ways. First, he was brought out of retirement, when he was on the verge of becoming a pujari in a temple, to become PM. He was not a natural leader of his party when he became PM, a situation similar to Indira’s in 1966.

He had to stage the April 1992 session of the All-India Congress Committee, risking a split while fighting detractors, to acquire a semblance of control over his party. PV had to earn the displeasure of Sonia Gandhi and her coterie.

PV had to wage these political battles even as he managed an unprecedented economic crisis and a sudden change in the global security environment with the implosion of the Soviet Union.

Few today understand the seriousness of the economic crisis that gripped the country between October 1990 and June 1991, with India on the precipice of external debt default for an entire two months, mortgaging gold to stay afloat.

Few also understand the loss of national confidence when the Soviet Union suddenly disappeared and the United States, a country closer to China and Pakistan than to India at that time, became the sole superpower.

Pulling the country back from the precipice, PV offered clever, if not bold, political leadership to fundamental changes in economic policy. Most of the ideas were all there in many academic studies and government reports but neither Indira nor Rajiv had the political courage to implement them.

PV provided the political cover that enabled Manmohan Singh and P Chidambaram to pursue policy changes. More importantly, PV himself took the initiative as minister for industry, to end the infamous licence-permit-control Raj that the Nehru-Gandhi darbar presided over for over three decades.

The policies PV put in place have since been continued by successive governments, though there has been some reversal on the trade front in recent months.

Reconfiguring Indian foreign policy to meet the needs of a post-Cold War world, PV built stronger relations with the US and the European Union and launched a Look East Policy, beginning with Singapore, that has stood the test of time.

PV was the architect of a new equation with East Asian nations, Japan and South Korea, with South and West Asian neighbours and with Israel. Each of these pivots created lasting good relations with a range of rising powers.

The main charge against PV has been that he was complicit in the destruction of the Babri Masjid in 1992 and, earlier in 1984, had not stepped in as home minister to prevent the killing of Sikhs in Delhi after Indira Gandhi’s assassination.

The facts do not merit either charge. In 1984, he was explicitly told by the Prime Minister’s office that the PMO would handle the Delhi situation. His inactivity at the time was an act of omission, not commission. There are other Congressmen who have to bear that cross.

In 1992, the entire Union cabinet met and resolved that the Union government would allow the state government of Uttar Pradesh to deal with the ground situation in Ayodhya and that the Centre would not impose President’s rule pre-emptively.

However, these errors of judgement on PV’s part will have to be weighed against the immense weight of his contribution to post-Cold War economic development and foreign policy. Finally, there is the matter of India’s nuclear weapons status. Many PMs have played a role in India’s emergence as a nuclear power. The credit for giving the green signal for the Pokhran-II tests should, even in the words of Vajpayee, go to PV.

It cannot be anyone’s case that there were no flaws in PV’s character or faults in his leadership. That could be said for almost any politician in a democracy. It is, however, a travesty of justice that PV’s contribution remains ill-acknowledged and inadequately celebrated.