- India adopted a calibrated approach best suited for a resilient recovery of its economy from COVID-19 pandemic impact, in contrast with a front-loaded large stimulus package adopted by many countries

- Expenditure policy in 2020-21 initially aimed at supporting the vulnerable sections but was re-oriented to boost overall demand and capital spending, once the lockdown was unwound

- Monthly GST collections have crossed the Rs. 1 lakh crore mark consecutively for the last 3 months, reaching its highest levels in December 2020 ever since the introduction of GST

- Reforms in tax administration have begun a process of transparency and accountability and have incentivized tax compliance by enhancing honest tax-payers’ experience

- Central Government has also taken consistent steps to impart support to the States in the challenging times of the pandemic

Does Growth lead to Debt Sustainability? Yes, But Not Vice- Versa!

- Growth leads to debt sustainability in the Indian context but not necessarily vice-versa:

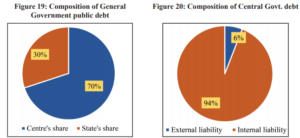

- Debt sustainability depends on the ‘Interest Rate Growth Rate Differential’ (IRGD), i.e., the difference between the interest rate and the growth rate

- In India, interest rate on debt is less than growth rate – by norm, not by exception

- Negative IRGD in India – not due to lower interest rates but much higher growth rates – prompts a debate on fiscal policy, especially during growth slowdowns and economic crises

- Growth causes debt to become sustainable in countries with higher growth rates; such clarity about the causal direction is not witnessed in countries with lower growth rates

- Fiscal multipliers are disproportionately higher during economic crises than during economic boom

- Active fiscal policy can ensure that the full benefit of reforms is reaped by limiting potential damage to productive capacity

- Fiscal policy that provides an impetus to growth will lead to lower debt-to-GDP ratio

- Given India’s growth potential, debt sustainability is unlikely to be a problem even in the worst scenarios

- Desirable to use counter-cyclical fiscal policy to enable growth during economic downturns

- Active, counter-cyclical fiscal policy – not a call for fiscal irresponsibility, but to break the intellectual anchoring that has created an asymmetric bias against fiscal policy

Does India’s Sovereign Credit Rating Reflect Its Fundamentals? No!

- The fifth largest economy in the world has never been rated as the lowest rung of the investment grade (BBB-/Baa3) in sovereign credit ratings:

- Reflecting the economic size and thereby the ability to repay debt, the fifth largest economy has been predominantly rated AAA

- China and India are the only exceptions to this rule – China was rated A-/A2 in 2005 and now India is rated BBB-/Baa3

- India’s sovereign credit ratings do not reflect its fundamentals:

- A clear outlier amongst countries rated between A+/A1 and BBB-/Baa3 for S&P/ Moody’s, on several parameters

- Rated significantly lower than mandated by the effect on the sovereign rating of the parameter

- Credit ratings map the probability of default and therefore reflect the willingness and ability of borrower to meet its obligations:

- India’s willingness to pay is unquestionably demonstrated through its zero sovereign default history

- India’s ability to pay can be gauged by low foreign currency denominated debt and forex reserves

- Sovereign credit rating changes for India have no or weak correlation with macroeconomic indicators

- India’s fiscal policy should reflect Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore’s sentiment of ‘a mind without fear’

Sovereign credit ratings methodology should be made more transparent, less subjective and better attuned to reflect economies’ fundamentals